Power and Christian Mission

It was 1996, and our U.S.–based team sat in a circle discussing the results of our emotional intelligence (EQ) assessments during a monthlong training for vocational ministry overseas. We were told these tools would guide us in choosing a team leader, but it quickly became clear that our decision was shaped less by data and more by each person’s cultural and theological imagination.

Years later, as a seminary student, I found myself in a similar discernment setting. Although new tools, such as conflict-style assessments, had been added, we lacked language for how power was being internalized and externalized—or how our theological assumptions about power influenced our discernment.

Now in 2025, after thirty years in ministry, I facilitate those same assessments with students who are preparing for vocational ministry. Yet in each era, one question has remained: Where, in our exegesis of ourselves, our contexts, and our theologies, do we find tools for understanding power?

If Christian mission truly flows “from everywhere to everywhere,” then we must consider how power dynamics shape that flow in and around us.

Mission history and present-day headlines underscore the need for what I call “power intelligence,” or the capacity to recognize how we conceptualize, internalize, and externalize power. Nineteenth-century historian Lord Acton famously warned religious and political leaders alike that “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” That reflection calls for Christians who can engage power with ethical integrity and theological clarity. But are we any closer to understanding what it is about power that corrupts? Is it how we understand power? How we use it? Who we become when we have it?

Although there are many types of power that warrant study and conversation, for the purposes of this article, theologian Bernard Loomer offers a clear definition: power is “that which is manifest wherever two or more people are gathered and have any kind of relationship.” Power isn’t limited to titles or positions—it is present in every relationship, whether in families, churches, or communities. If Christian mission truly flows “from everywhere to everywhere,” then we must consider how power dynamics shape that flow in and around us.

How Power Is Internalized

If you lived in the United States in the 1980s, you may remember the Partnership for a Drug-Free America’s ad campaign: an egg, a frying pan, and the captions, “This is your brain,” “This is drugs,” “This is your brain on drugs.” It’s an apt metaphor for what psychology and neuroscience have revealed about what happens to our brains “on power.”

The renewing—or rewiring—of our minds is not a new concept in Christian thought. The apostle Paul speaks of it in Romans and Ephesians. Over the last fifty years, researchers have shown that power differentials can literally reshape our “minds.”

Power can reduce our empathy and narrow our perspective. Brain-imaging studies show that when power differentials exist, those with more power tend to display reduced motor resonance when observing others’ actions—a sign of diminished empathy. They are also less likely to consider others’ viewpoints or accurately read emotions. Researchers concluded that “power leads individuals to anchor too heavily on their own vantage point, insufficiently adjusting to others’ perspectives.”

Power can distort our judgment. Other studies show that people in positions of power tend to exhibit high confidence in their decisions, even when unwarranted, resulting in reduced accuracy. Overconfidence persisted across experiments, even when participants were incentivized to be correct.

Power can lead to detachment. Psychologist David Kipnis’s classic 1972 study, “Does Power Corrupt?” found that people with power often devalued subordinates and used coercive tactics, viewing others as tools. Later researchers described “hubris syndrome,” a disorder marked by pride, impulsivity, contempt for questions, and detachment from reality—symptoms seen in leaders who become insulated by privilege.

Their findings suggest that prolonged power advantages can alter personality and perspective, and damage judgment. These patterns raise questions about what power’s rewiring of the mind looks like across generations—and what forms of spiritual and communal intervention are needed.

How Power Is Externalized

While psychology reveals power’s internal effects, political and social theorists have long examined how it manifests externally. From Hannah Arendt on collective action to Michel Foucault on institutional control, they highlight power’s many forms.

Institutional and systemic expressions of power become what theologian Walter Wink calls “the powers that be.” Yet even around church committees or family tables, smaller but significant power dynamics emerge. Sociologists describe these as dimensions of power.

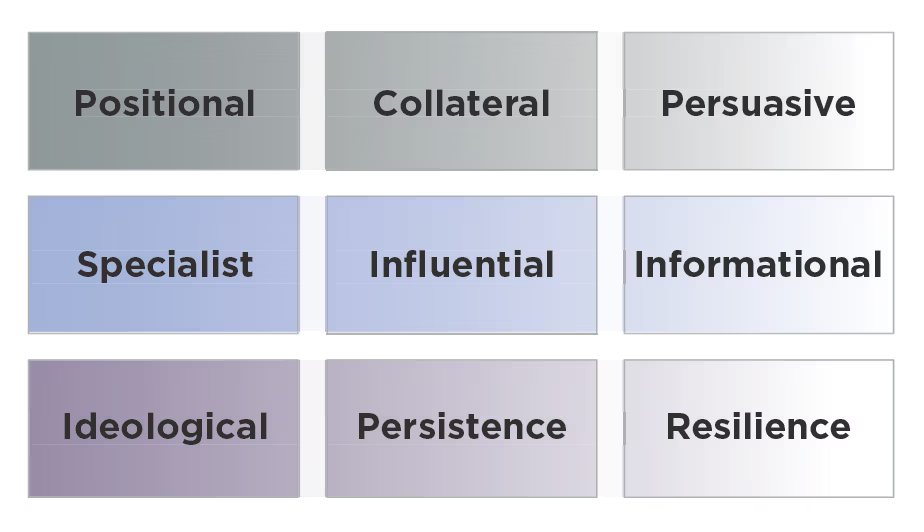

Positional or institutional authority is the most visible, but many other dimensions are more easily felt than named: the influence of donors, experts, ideologies, or charismatic individuals. In workshops, I often ask participants, “What forms of power are easiest to see in yourself or others?” and, “What forms have you never considered?”

How Power Is Conceptualized

Recognizing the ways power differentials affect both people in a power dynamic is an important aspect of power intelligence, as is understanding the different dimensions of power that are at work. However, the aspect of power that is perhaps the most hidden is how we interpret our exercise of power. For Christians, this often comes through our theological lenses or frames for power. Yet as theologian Stephen Sykes reminds us, “Power is not eliminated by noble purpose.” Christians would be healthier by acknowledging our power narratives rather than disguising them. Below is a brief summary of how the Christian imagination has wrestled with power for centuries.

The author’s adaptation of John French and Bertran Raven’s “Bases of Social Power” (1959) expanded Arash Abizadeh’s “The Grammar of Social Power” (2023).

Divine versus earthly power. Augustine of Hippo described the “two loves” of the City of God and the City of Man, contrasting divine and human power. This developed into Martin Luther’s “Two Kingdoms Theory,” distinguishing spiritual authority (the church) from secular authority (the state). More recently, David Fitch in Reckoning with Power calls Christians to use power to serve rather than dominate, with a critical eye toward political power.

Moral/immoral power. Perhaps the most significant representation of this lens is found in Reinhold Niebuhr’s Moral Man, Immoral Society. He argues that while individuals can act morally, society—particularly in its institutional forms—often acts immorally, driven by power, self-interest, and the dynamics of collective action. Stanley Hauerwas emphasizes Christian character in navigating nationalism and coercive power.

Oppressive versus liberating power. Liberation theologians amplify the voices of the oppressed by declaring Jesus’s preferential option for those on the margins. Gustavo Gutiérrez reminds us that oppressive conditions are not inevitable: “His or her existence is not politically neutral, and it is not ethically innocent.” Jon Sobrino adds that love and justice are best understood through solidarity with the oppressed, while womanist theologian Delores Williams frames this solidarity as resistance.

Ordering versus disordering power. Walter Wink explored how “the powers” function as both spiritual and structural realities—the inner and outer aspects of material and ideological institutions. For Wink, the goal is not to destroy power but to transform it. Uncritical loyalty becomes idolatry; violence is reordered through nonviolent love.

Inclusive power versus exclusive power. Willie Jennings argues that power used for something other than belonging leads to fragmentation. True Christian power nurtures human flourishing and restores community, engaging other disciplines to confront the lingering effects of patriarchy and colonization.

Most of us resonate with at least one of these frameworks. We can hear them echoed in sermons, podcasts, and politics. They shape and clarify our imagination of how power should operate in the world. Yet they can also obscure reality.

Like political binaries, theological dualisms can create conditions for the misuse of power as one inevitably locates and justifies oneself as being on the “right side” of power, bypassing what power does to the person holding or exercising it. This, I believe, is the beginning of power intelligence for Christian mission: recognizing the narratives we hold about our own power, which can keep us from interrogating how power is being externalized or internalized. It’s not only about understanding “the powers that be,” but also discerning how our imagination around power both clarifies and conceals its effects and our decisions.

Much like the opening story of who would lead our mission team, it was each person’s theological imagination that shaped their discernment, even when other overt rubrics were named. History and headlines serve us even more examples of how our imagination around power’s use motivates and mars decision making. This should lead us to ask a crucial question: Does my understanding of power lead to the flourishing of everyone and corruption of no one? What interventions are necessary to ensure this is the case?

How Power Is Rewired

With a history of mission organizations “from the West to the rest,” mission “from everywhere to everywhere” will need to both interpersonally and structurally assess our own power narratives and dynamics in order to renew, not only our minds but the way we do mission. Yet Scripture reminds us that as much as we can be affected and conformed to this world, our minds can be renewed. In fact, knowing how our minds are being wired offers insight into what intervening habits can rewire and renew our minds (and mission!). These practices and values are not new encouragements for followers of Jesus, but the research does highlight how crucial these practices are.

Engage opportunities to increase empathy and perspective taking. If research shows that power differentials can lead us to “anchor too heavily on our own vantage point,” what practices do we employ to hear from people with different experiences and perspectives? How do we mitigate or acknowledge power dynamics in that listening process? Whether in our households, houses of worship, or holistic mission initiatives, do we encourage practices of listening to each other, especially from those who were most affected by our decisions? What outlets are “hardening our hearts”? What practices can soften them? Do we engage intentional, immersive discipleship experiences like our regional Journey to Mosaic weekends, Sankofa, Immigration Immersion at the Border, Weaving Justice and Peace with North American Indigenous leaders, or global Merge opportunities? What ways can you engage other perspectives this year?

Create mechanisms to clarify judgment. In our relationships, churches, and organizations, how are decisions made? What feedback loops exist? How do we interpersonally and systemically normalize reflection so not all conversations are reactive? How do we welcome reflection on decisions and discernment? Are our second sets of eyes people who can disagree with us without consequence?

In our theological reflection modules, we use the biblical metaphor of sheep to ask, who can really tell you what’s gotten stuck in your wool? We know who to call to tell us we’re in the right, but do we call whoever will tell us when we’re at a tipping point? Organizationally, those who can see where our vision is obscured are often those who are newest to the flock or closest to the margins.

Practice habits that hone humility. As Dennis Edwards writes in Humility Illuminated, humility is a way of life. The book of Philippians tells us that Jesus models a yielding, reconciling, sacrificing, enduring, and empowering spirit in part by not considering equality with God something to be grasped but by soberly embracing the limits of being human. Often defensiveness and dogmatic postures signal that we are grasping for a rightness only God can claim. Similarly our worldviews of innocence/guilt, honor/shame, or power/fear can filter how we hear and see ourselves, a situation, or a perspective that is different from our own. Engaging tools, rhythms, and practices of self-awareness will help us remember what we are bringing to a situation, both the gifts and limitations.

Part of humility is also recognizing that our theological imagination around power will both clarify and obscure how power is at work. If our values are being realized, we are probably less likely to ask if the power exercised is empowering everyone and corrupting no one. Seeing both our own gifts and limitations and the gifts and limitations of our theological lenses can help hone the type of humility necessary for our work as mission friends.

Mission history offers us both caution and hope. It records moments when Christians idolized power—and moments when believers courageously resisted its distortions. The renewing of mission in our time will require not only a rewiring of our minds but practices of discernment and confession where we can acknowledge where power has wounded and continues to wound. With a gospel that addresses our guilt, shame, and fear, we are well resourced for this work! With Jesus as our guide and the Holy Spirit as our help, we don’t engage this renewal alone. Let us press on for the joy set before us and be unafraid to ask ourselves how power is at work in everything, everywhere, all at once. For God’s Spirit longs to renew our minds, our mission, and our world.

This article was first published in the Covenant Companion Winter 2026 issue, the official magazine of the Evangelical Covenant Church.