How the Covenant Responded to the Black Manifesto

As humans we are always stepping into the middle of a developing story. Everything that comprises our common life as Covenanters—our congregations, structures, commitments, and conversations—is shaped by histories that precede us. These histories explain, inspire, caution, and empower. Above all, in their complexity they remind us that the gospel has only ever been lived out by imperfect persons in a messy world. We are called to be the church in this hour, recognizing that our present will be someone else’s past.

This recurring feature will highlight snapshots from our denomination’s rich story. Knowing this past can help us build well in the present, in active hope for the future.

“No institution in American society has confessed its guilt as often as the church. It has written ten thousand empty pronouncements regarding social justice. If reparations are really an acceptable form of repentance, then white American churches have the duty to express their sincerity by repaying their debts which have accrued through slavery and black subjugation.”

These words are not from an op-ed on Georgetown University’s recent student vote for reparations or from the 2020 campaign trail but from an article published in this magazine 50 years ago. They were written by Worth Hodgin, Covenant pastor and then-director of urban ministry for the Central Conference. Hodgin’s article, “Reparations,” was one of four pieces responding to the Black Manifesto that together comprised the cover story of the August 1, 1969, Companion.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Black Manifesto. Written by James Forman and adopted at the National Black Economic Development Conference (BEDC) on April 26, 1969, the Manifesto issued a demand for $500 million from white churches and synagogues, as reparation for their complicity in four centuries of black economic exploitation. The text outlined a ten-point plan for economic development with revolutionary rhetoric that called for violence if necessary.

The document sent shockwaves through white churches and synagogues when the Manifesto’s call for the disruption of white worship services was set in motion on May 4. Entering the Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York City, Forman read the Manifesto as the organ sought to drown him out and Pastor Ernest Campbell walked out of the church along with two-thirds of the congregation. Throughout that summer, Forman and other BEDC representatives brought their demands to other white Christian and Jewish groups across the country, including the Evangelical Covenant Church of America, as the denomination was then called.

The Covenant Executive Board came to the denomination’s 1969 Annual Meeting at North Park College in Chicago prepared. Anticipating the likely appearance of a BEDC representative, they presented a preemptive proposal early in the meeting recommending that the Covenant establish a “fund for poverty-stricken black Americans.” A goal was set to raise $335,000 over five years, asking every Covenanter to double his or her $1 World Relief offering. The relationship of the action to the Black Manifesto was made explicit in the proposal; however, its connection to the intent of the Manifesto would be muted later. Although not sympathetic either to the revolutionary rhetoric of the Manifesto or the idea of reparations, the Executive Board recognized the gravity of the need and sought to take positive action, if admittedly modest.

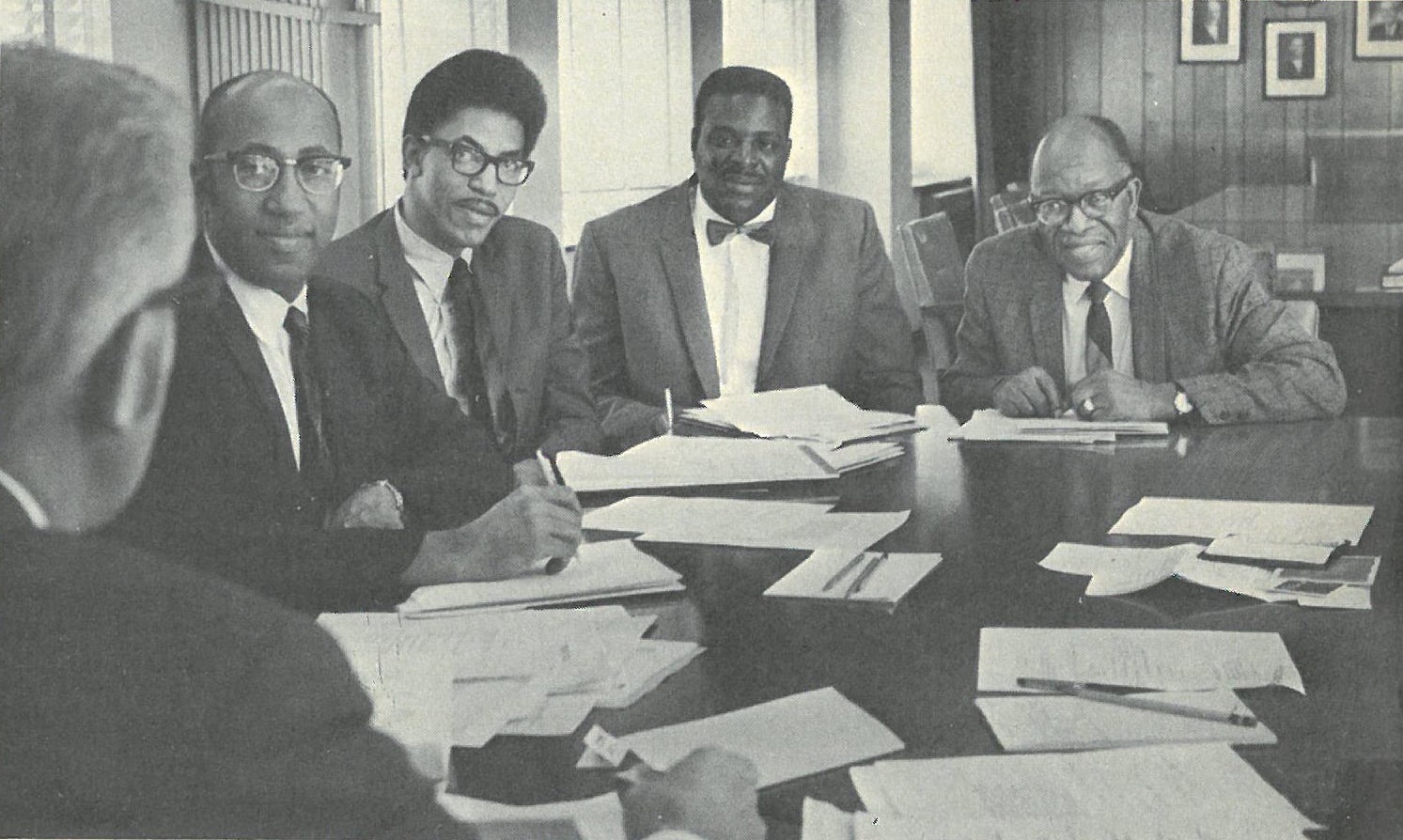

Members of the committee to oversee the fund established by the 1969 Annual Meeting in response to the Black Manifesto meet with then president Milton Engebretson (far left). The committee from left: J. Ernest DuBois (Emmanuel Covenant, Rochester, New York); Robert L. Sloan Jr. (Community Covenant, Minneapolis); Robert Dawson (Grace Covenant, Compton, California); and Nathan Brown (Oakdale Covenant, Chicago).

Significant discussion followed. Several amendments were proposed from the floor, each of which was discussed at length. Debate exhausted one business session and spilled into the following day’s agenda. Of the many amendments proposed, only one was adopted: the new fund would not be directed by the Commission on World Relief, as originally proposed, but rather by “a committee of Black Covenant men and women.” With this revision, the delegates voted to approve the fund.

At the end of Saturday’s business, Herman Holmes Jr., Midwest director of the BEDC, arrived at the meeting, uninvited but not unanticipated. President Milton Engebretson introduced Holmes to the delegates and gave him the floor. Before reading the Manifesto’s demands, Holmes introduced the document in the context of Christian justice, cautioning delegates against focusing only on its controversial language. As he exited the stage, delegates applauded—some with a standing ovation—and the moderator adjourned the day’s business with a closing prayer. Hodgin and Craig Anderson, pastor of Oakdale Covenant Church in Chicago, invited Holmes to George’s diner on Foster Avenue for coffee and continued conversation. A summary of responses to the Manifesto written in July 1969 singled out the Covenant’s reception of Holmes as “the only BEDC encounter with a church which was not stormy at some point.”

The Covenant’s response offers a snapshot of a church in transition.

Engebretson opposed the Manifesto’s revolutionary rhetoric and tactics—which was the response of most white Christian groups, even those who accepted its indictment. Given this opposition, it is notable that he did not allow the Covenant to dismiss the Manifesto’s content by reacting solely to its rhetoric—the response of most white evangelical groups. Instead, he affirmed the complicity of the white church in racism and the urgent need for an active, constructive response.

A summary of responses to the Manifesto … singled out the Covenant’s reception of Holmes as “the only BEDC encounter with a church which was not stormy at some point.”

The Manifesto called out the American economy as the product of black slavery and ongoing economic disempowerment of African Americans. It named white Christians as the beneficiaries of this centuries-long system of exploitation and called on them to make material repair as a matter of justice.

The Covenant fund, however, was an act not of justice but charity. It addressed the problem of generic poverty rather than the unjust distribution of wealth. Covenanters were called upon to give generously out of their abundance—with no acknowledgment that this very abundance was symptomatic of the systemic injustice the Manifesto named. They sought, through their voluntary generosity, to be part of the solution; yet they did not see themselves in the problem—they did not see themselves as debtors.

Given the Covenant’s focus on poverty rather than particular historical injustices, it is not surprising that the scope of the new fund was quickly broadened and thereafter named “Fund for Disadvantaged Americans of Minority Groups.” (In 1983 the fund was renamed Hands Extended Lifting People—HELP—and in this form persisted to the end of the twentieth century.)

Not all Covenanters rejected the Manifesto or the call for reparations. A group of young pastors met several times in advance of the Annual Meeting to discuss the direction of the Covenant and to strategize responses to pressing issues—topping their agenda was the Black Manifesto. This group’s initiative and advocacy led to the fund being administered by black Covenant leaders—the only point consonant with the spirit of the Manifesto.

After the Annual Meeting, conversation continued in the pages of the Companion. In addition to President Engebretson’s report on “The Annual Meeting Decision on Aid to Black America” and the full text of the Manifesto itself (though not its fiery introduction), the magazine ran three pieces of commentary: 1) Worth Hodgin’s historical and theological case for reparations; 2) black Covenanter and chair of Community Covenant Church in Minneapolis Robert L. Sloan Jr.’s “Force and Violence,” urging Covenanters to recognize violence as a symptom of injustice and to listen first to oppressed communities when they named those injustices; and 3) “Financial Control,” by North Park Seminary professor Wesley Nelson, encouraging Covenanters to embrace the possibilities opened up by black Covenant leadership. Nelson suggested that the Covenant’s post-emancipation immigrant origins, small size, and modest financial assets were potential benefits to this new partnership, even as he acknowledged, “ doesn’t make us any less racist.” He called for the church to embrace the opportunity with faith, adding, “To work with black leaders in the distribution of funds we have raised could open the doors of mission in a way we have never known before.”

Engebretson’s presidential report similarly pointed to new possibilities for the Covenant. It concluded, “If the sobering events of our time are successful in bringing the Church of Jesus Christ to its knees in repentance before God, resulting in the salvation of the lost and reclamation of the needy, we of the Covenant may be standing on the threshold of our finest hour.”

While the degree to which the church was brought to its knees in repentance may be debated, there is no doubt that 1969 constitutes a threshold in Covenant history.

The Covenant’s response offers a snapshot of a church in transition.

As delegates gathered for the 84th Annual Meeting, the church had barely moved beyond its origins as an ethnically Swedish denomination. Only one generation prior, the church bore its original name, Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant in America, indicative of its identity as an immigrant people in a foreign land. When the name was altered in 1937 to Evangelical Mission Covenant Church of America, the change was in large part aspirational: at the time only 17 percent of congregations were worshiping solely in English. Pastors retiring in 1969 had been trained to preach in English and Swedish in order to serve an ethnic immigrant church. Just 14 years earlier, denominational publications began printing exclusively in English. In 1969 only a handful of congregations had partial or predominant African American membership, and Robert Dawson was the only African American member of the ministerium. The following January, Willie Jemison would begin his three decades of ministry at Oakdale Covenant in Chicago.

One generation later, the theme of the 1999 Midwinter and Annual Meeting was “Celebrating Our Ethnic Diversity.” No less than the Covenant’s name change in 1937, this theme was more aspirational than actual. That decade had witnessed the new requirements of ethnic representation on denominational boards (1993) and the formation of the Black Pastors’ Council (1992) and the Commission on Ethnic Ministry (1995), comprised of chairs of formalized ethnic ministerial associations. The first Sankofa trip was taken in conjunction with that year’s Midwinter Conference.

In 1937 and 1999, both acts were symbolic. They did not represent a significant change in the makeup of the denomination. What they did was signal the church’s desire to expand its identity. To the degree these aspirations were realized—unevenly, imperfectly, and often amid conflict—it was the result of intentional, active responses to new contextual realities. In the space of two generations, the Covenant moved from seeking to break out of its immigrant enclave to seeking to more fully embrace increasing ethnic diversity. A thousand individual and corporate decisions, initiatives, and actions lie between those chronological poles, comprising the complex chain of causality that is history.

Fifty years ago, the Black Manifesto called white churches to responsibility. Fifty years later, the call still stands.

For further discussion, see this issue of The Covenant Quarterly which marks the 50th anniversary of the Black Manifesto.