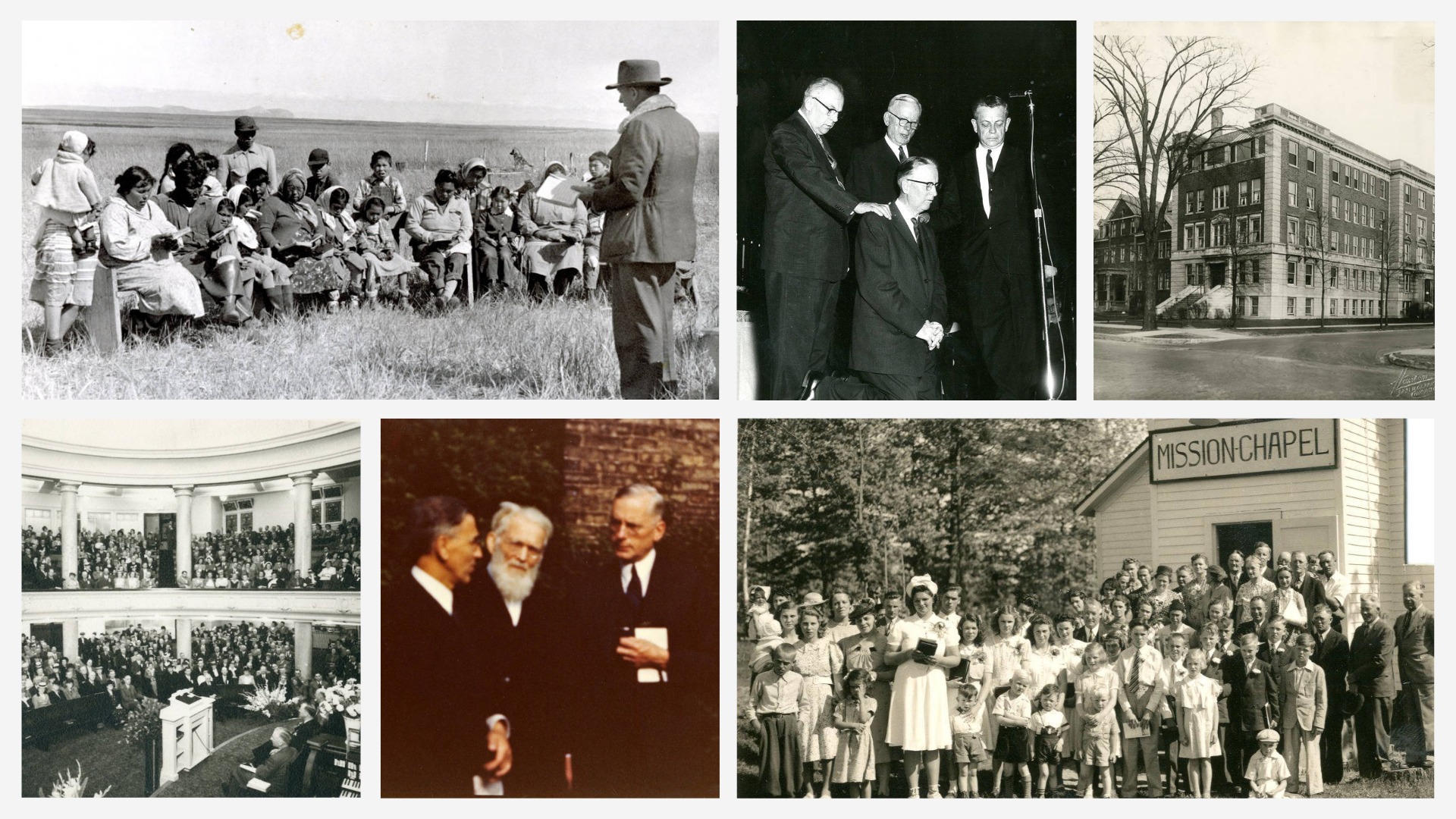

This text was originally delivered as the inaugural lecture when Dr. Hauna Ondrey was named the Wilma E. Peterson Chair in Church History at North Park Theological Seminary—photos provided by the Covenant Archives.

It is an honor to be installed in the newly created Wilma E. Peterson Chair in Church History. It is especially poignant and fitting that this endowed position for history is made possible by a woman whose lifetime of service and generosity exemplifies the quiet faithfulness that makes up so much of history, especially the history of the church. The decision of North Park’s senior leadership to allocate an endowed position to history, with a dedicated emphasis on denominational history, is also highly significant at a time when universities and seminaries are cutting history positions and curricula, and denominations are muting historical roots—even as historical amnesia is especially prevalent and historical understanding especially needed.

While this role is new, the decision to formalize North Park’s commitment to the history of our denomination honors the critical contributions of Covenant historians who have worked faithfully across the entirety of our school’s history: David Nyvall, Eric Hawkinson, Karl Olsson, Glenn Anderson, and my predecessor, Philip J. Anderson. We are indebted to the careful, purposeful work of these historians to root us in collective memory. Their work in turn has depended on our archivists, both non-professional—John Peterson, E. Gustav Johnson, Eric Hawkinson, Milton Freedholm, and Sigurd Westberg—and professional—Timothy J. Johnson, Ellen Engseth, Steven Elde, Anne Jenner, Anna-Kajsa Anderson, and Andy Meyer. Each dedicated archivist has built on the work of the previous, with the support of the Covenant History Commission, as we will see in this article.

Purposeful Narrative

In 2004, the Evangelical Covenant Church adopted the Fivefold Test (more recently expanded to the Sixfold Test to include practicing solidarity). The goal of the test was to move past viewing demographic diversity as a matter of numbers only (i.e., the first “p” of population) and to ensure true diversity in the very fabric of the denomination through attention to participation, power, pace-setting, and purposeful narrative. Purposeful narrative asks, “How do the stories of new backgrounds become incorporated into our overarching history? How do all of these streams flow together into one story moving forward?” This continues to be a crucial question for a denomination founded by Swedish immigrants that now boasts 36 percent of its current congregations as “ethnic” or “multiethnic.” Yet in the two decades that have passed since 2004, the call to purposeful narrative has been frequently invoked but rarely enacted.

My primary goal in this article is to contextualize the call to purposeful narrative within Covenant history and to concretize the corollary commitments that are prerequisite to its actualization. Taking as settled the admittedly disputed point that historiography matters, I want to focus on how historiography happens, the larger infrastructure that enables history to be written at all. I will do this through snapshots of the intersection of denominational identity and historiography at key anniversaries—the fiftieth anniversary in 1935 and the centennial in 1985—ending by looking ahead to the Covenant’s 150th anniversary (2035), raising the urgent question: will we be able to tell any narrative of the preceding half century—and will Covenanters in 2085 be able to tell the story of the church we are creating today?

Narrating and Preserving Covenant Memories: The Fiftieth Anniversary (1935)

Anniversaries—especially big anniversaries like quarter-centuries and half-centuries—tend to generate historical reflection. They cause groups to take stock of the paths of change and continuity that have led to their current identity at the milestone and to consider which aspects of that past they want to carry into the future. This was true of the Covenant as it gathered to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary in 1935, a time of monumental transition in the life of the young denomination. The Covenant was in 1935, comprised of 430 congregations (totaling 44,153 members), 70 percent of which still had “Swedish” or “Scandinavian” in their church name.

Since the First World War, the Covenant’s original ethnic boundary had begun to erode. Fewer and fewer Swedes emigrated, at times more making the reverse journey back to Sweden. Wartime restrictions on non-English languages pushed second-generation pastors with greater English language facility into more prominent positions of leadership. Most pressingly, denominational leadership noted with alarm the number of young people leaving Covenant congregations, which were ill-equipped to meet the needs of an English-speaking, more culturally American second generation.

Two years prior to the fiftieth anniversary celebration, T.W. Anderson had been elected as the first American-born Covenant president. Fully bilingual in Swedish and English, Anderson was well-suited to lead the denomination in the transition it faced as the founding generation gave way to second-generation leaders, and English increasingly eclipsed Swedish as the denomination’s lingua franca. At the 1935 celebratory Annual Meeting—only the sixth conducted fully in English—the Covenant would vote to remove “Swedish” from its denominational name, moving from “Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant in America” to “Evangelical Mission Covenant of America.”

Many historical publications were produced in preparation for that anniversary celebration, most notably Covenant Memories. This massive undertaking, which the Board of Publications described as “a laborious task for our editors and a costly undertaking for the Board,” compiled contributions from no fewer than twenty-four authors. Hjalmar Sundquist provided an overview of denominational history (“The Mission Covenanters: An Outline of History”), divided equally between the “Swedish Background,” “The American Background,” and “Fifty Years of Service.” This was followed by histories of every Covenant institution (North Park, Covenant Hospital, and Home of Mercy), regional conference (then thirteen), and ministry, both domestic (youth work, publications, etc.) and international (then Alaska, China, Congo)—each contributed by an appointed historian from these ministries and each offering a distinct piece of Covenant history.

The monumental Covenant Memories volume represents the work not only of the twenty-four authors (and laborious work of their editors!) but also the result of broader community efforts to collect the materials necessary to write the compiled accounts as well as later historical projects made this possible. The Middle East Conference, for example, had a four-person committee gathering historical records. In that process, the conference secretary also compiled brief historical sketches of not less than 23 of our churches from the material furnished by the statistics collected. That document is of great historical value for the conference as well as for the churches and future historians.”

In addition to this multiauthor history, anniversary editions were issued by the youth annual Our Covenant as well as Phoebe, the publication of the Covenant Women’s Auxiliary. Congregational anniversary histories proliferated in the decade surrounding the denomination’s fiftieth anniversary—with fifty-eight available digitally in the non-exhaustive Covenant Archives collection. A more extensive history of North Park College was also prepared for the school’s fiftieth anniversary, which followed soon after in 1941.

President T.W. Anderson framed the historical changes and continuities described in the pages of Covenant Memories in his opening essay, “Covenant Principles.” Anderson begins by noting the significant changes that had taken place in the half century of the Covenant’s history, pointing especially to the shift to English following the reduced flow of immigration and a new focus on youth. This, he writes, “is inevitable and not necessarily regrettable. Living movements are not static but adapt themselves to new conditions.”

But then he points to the Covenant’s fundamental principles, which remained unchanged. These he names as “the supremacy of the Bible,” “the necessity of spiritual life,” “belief in the unity of all true Christians,” “the independence of the local church,” and “the urgency of the missionary task.” In the final section on Covenant home mission, Anderson indicates a shift in Covenant home mission enabled by the collapse of the language barrier, and he celebrates the new mission field this opens to the Covenant, its domestic work no longer limited to Swedish language speakers. He exclaims,

With the language barriers eliminated, there are open doors on every hand. Free from sectarian bias, believing in the church as a spiritual home for all Christians, the Covenant is particularly qualified for this frontier work. Emphasizing the central truths of the historic Christian faith, as we earnestly desire to do, we are convinced that God has a commission for us at our very doors. The greatest opportunities in the half century of our brief history are challenging us.

In the earlier language debates, many who resisted the transition to English were concerned that the Covenant would lose its purpose if it was no longer a Swedish immigrant denomination serving the Swedish immigrant community. Notice then what Anderson does in leading the Covenant through this critical transition: he grounds the Covenant in its founding identity as a mission organization and celebrates the expanded mission field opened by the Covenant’s new capacity to worship, serve, and evangelize in English. Notice too that he frames the particular purpose of the Covenant as a faith community, not in its ethnic identity but precisely in terms of its founding “Covenant principles”: its non-confessionalism and believers’ church ecclesiology. This, he says, is the essential identity of the Covenant that it will take from its past into the next fifty years. The shift from Swedish to English, far from threatening the Covenant, instead would open the greatest opportunity the Covenant had yet known.

In his presidential report, T.W. Anderson encouraged every Covenant home to acquire, read, and appreciate the history painstakingly collected in the pages of Covenant Memories, which in the foreword he dedicated to the Covenant youth. He said of the volume, “We are not ancestor worshippers, but we do recognize gratefully our debt to the trailblazers of fifty years. We want to study the past in order that we may better understand the present and, by the grace of God, plan wisely for the future.”

In addition to the historical work invested in preparation for the milestone celebration, at this fifty-year anniversary, the denomination made deliberate provisions for the collection and care of archival records to enable ongoing historiography as it lost the living memory of the founding generation. The 50th Annual Meeting established a Covenant Historical Commission to collect and steward the historical records of the church through a Covenant archives. Covenanters from across the denomination were requested to send books, letters, meeting minutes, photographs, and other records of historical interest—and these items began to arrive in the hundreds.

The five-person Covenant Historical Commission immediately expanded their team with Gerard Johnson becoming the de facto archivist, cataloging and filing the vast materials received, and with the appointment of a Commission representative within each district conference to collect additional material for the central denominational archive. Each year, the Commission thanked those who had donated materials and repeated its appeal for historically valuable documents. “The Commission wishes to repeat its appeal to all Covenanters to save and send to the archives old letters, photographs, diaries, records, and memorabilia of Covenant enterprises, pioneers, and local churches. Even seemingly insignificant items may be of value in preserving some phase of Covenant history.”

As those documents multiplied, the pressing need for space became a refrain in Commission reports. The documents collected were housed both in Old Main on North Park’s campus and at Covenant Offices, eventually converging on campus. At one point, all organization of materials halted as the collection was moved off campus due to space constraints. Even when limited in resources, the Commission continued the tedious, foundational work of source collection in preparation for the time an adequate space would be available: “The work which was done by Gerard Johnson some years ago and is now being continued by I.W. Jacobson is all in preparation for the day when adequate facilities are made available for the caring of these records. In the meantime, we shall continue our task of gathering, classifying, indexing, and preserving historical materials best we can.” That work continued in faith for fourteen years until the Wallgren Library opened in 1958 and the Covenant Archives gained a dedicated space in Nyvall Hall.

Through the work of an active History Commission and dedicated volunteer archivists, sources were collected, organized, translated, and interpreted through commissioned publications. The Commission and its humble archives supported the research leading to historical publications and generated publications of their own almost immediately, translating works and issuing biographies of key leaders, financed fully through sales.

In commemoration of its fifty-year anniversary, then, the denomination took proactive measures to narrate its history through commissioned, communal history-writing and to ensure its history would continue to be known into the new generation—collecting and preserving historical sources and commissioning a committee to superintend that work. This was a full church effort.

Circling into a Second Century: Covenant Centennial (1985)

The breakdown of the language barrier and resulting potential for an expanded mission field that President T.W. Anderson celebrated in 1935 became a reality over the next half-century. When the Covenant gathered to celebrate its centennial anniversary in 1985, its 584 congregations included growing numbers of African American, Spanish-speaking, and Korean-speaking congregations. This demographic expansion was in large part the result of intentional church planting and adoption efforts spearheaded by the Department of Church Growth and Evangelism, led by Robert Larson, who had named “ethnic ministries” the “issue of the decade” in the 1980s.

At the beginning of that decade, “ethnic churches” comprised 3.5 percent of total Covenant congregations; by the end of the decade, that proportion had more than doubled to 8 percent (numbering thirteen Korean-American congregations, twelve Indigenous, seven African American, seven Latino, and one Vietnamese). As the Covenant anticipated its one hundredth anniversary in 1985, it grappled again with its ethnic history and current identity, actively questioning how to effectively incorporate new ethnic communities, both European and non-European, and what role its own ethnically particular past should have, if any, in an increasingly multiethnic future—the realization of what T.W. Anderson had anticipated five decades earlier.

In 1979 the Covenant Annual Meeting had approved a “Resolution on Diversity,” which both “affirm[ed] the ethnic heritage of the Evangelical Covenant Church of America and its early ministry to persons of Swedish descent,” and resolved to “make a conscious effort no longer to assume Swedish-American culture to be the norm for the Covenant” in order to ensure hospitality to the increasingly diverse “national and cultural backgrounds” within the denomination. This resolution indicates the desire of that time to acknowledge that the demographic composition of the church had fundamentally shifted such that a shared ethnic past could no longer be assumed. This had implications for how the denomination spoke about itself, the jokes it told, and the languages it used.

In 1982, Covenant President Milton B. Engebretson presented to the Council of Superintendents a typology of a Covenanter, modifying an earlier typology offered by North Park President Lloyd Ahlem. Engebretson identified three subsets (or “circles”) of Covenanters. First-circle Covenanters identified with the Covenant’s Lutheran Pietist roots. They cared about theological education, social justice, and sacramentalism. Second-circle Covenanters aligned more closely with conservative American Evangelicalism, were more Reformed, and committed to biblical inerrancy, evangelism, and church growth. Third-circle Covenanters were relative newcomers who had “no investment in the history or heritage of the Covenant” and found its residual Swedish ethnic quality to be problematically overemphasized.

The 1979 resolution and “circles” typologies show a phenomenological reality that the growing demographic diversity of the Covenant raised critical questions about its ethnically particular past. Anticipating the centennial celebrations, Lloyd Ahlem feared that “third-circle” Covenanters—those who had joined amid the postwar growth—would feel they were simply “invited guests at someone else’s birthday celebration.” If a growing number of Covenant congregations and members did not share a common history, what was the implication for how the denomination told its own history as it made intentional investments to become more racially and ethnically diverse?

Attention to these questions is evident in the centennial publications commissioned. Karl A. Olsson, professor of English and North Park president (1959–1970), had emerged as the denomination’s preeminent historian, having been commissioned in 1955 to write a historical narrative to mark the denomination’s seventy-fifth anniversary, a request he acquitted seven years later with the commanding By One Spirit. Olsson offered a more accessible history for the ninetieth anniversary, Family of Faith, and was tasked with providing a similarly condensed updated account for the centennial, resulting in the two-volume Into One Body…By the Cross, the first volume appeared in time for the centennial and the second the following year.

At the same time, the records of the Covenant Centennial Committee reveal a desire to look ahead—and the conviction that Olsson was a figure of the past. The volumes commissioned sought to balance past, present, and future, with attention to the past intentionally muting the denomination’s Swedish roots. This is exemplified in the planned “Pictoral [sic] Volume” that never came to fruition: “Although it will be as historically accurate as possible, it will not emphasize ‘Swedishness’ as much as Covenant. It will therefore include involved ethnic groups, and a heavy section on ‘New Roots’—section V of the proposed book, which has yet to be refined.” In searching for a suitable author, discussion noted both that “to fail to invite K.O. to participate would be politically unwise” yet found his “literary style” inconsistent with the intention of the volume.

One of the commissioned centennial publications that did come to fruition addressed the role of the Covenant’s ethnic roots directly. The Mission of a Covenant was written by Paul Larsen, then serving as pastor of Peninsula Covenant Church in Redwood City, California. Larsen argued that the Covenant faced an “identity crisis with a capital ‘I,’” exacerbated by its continued attention to ethnic roots amid growing multiethnicity. He warned that “without transcending its own story, the Covenant will disintegrate.” Larsen’s book pursued that goal of transcendence by narrating Covenant history within a broader biblical pattern and a “theology of interior covenantalism” rather than Swedish immigration. Larsen sought to build a historical account from Engebretson’s phenomenological account of Covenant “circles,” arguing for the equal claim of first- and second-circle Covenanters (i.e., Lutheran and Reformed roots) within denominational history and argued that the Covenant’s “constructive future,” including the continued vitality of the third circle, depended upon a fruitful dialectic between the first and second circles, a proposal Larsen focused in his 1985 Nyvall Lecture at North Park Seminary.

In his contribution to Karl A. Olsson’s Festschrift, Covenant historian Philip J. Anderson systematically critiqued the implicit and explicit historical claims in Engebretson’s descriptions of the first and second circles as well as Larsen’s attempt to equalize them historically. Anderson argued that attention to historical sources required distinguishing Lutheran identity from Reformed influence in the self-understanding of early Covenanters. More fundamentally, Anderson challenged such typologies as unhelpfully static and phenomenologically rather than historically derived. Because they presented caricatures rather than accurate depictions of reality, they were ultimately unhelpful for understanding denominational pluralism and productively seeking unity within it. As an alternative, more dynamic image, Anderson offered David Nyvall’s identification of centripetal and centrifugal forces throughout Covenant history, which held in balancing tension the goods of denominational unity and congregational autonomy.

This historiographical debate between Paul E. Larsen and Philip J. Anderson suggests the ways in which Covenant history—especially its ethnically particular history—was contested at this time and the nascent impact on how that history would, or would not, be told. Moving forward from the denomination’s centennial, Anderson’s critique of Larsen’s proposal put a stop to classifying Covenanters according to circles and to re-narrating Covenant history in a way that demoted its particular roots in Lutheran Pietism. At the same time, the sense that the very particularity of those roots was an albatross to the denomination’s increasing diversity chilled denominational historiography. Moving forward from the centennial, people stopped talking about circles…and history stopped being attempted on any broad scale.

The centennial celebration program, held in Minneapolis, gestures to this trend. History certainly was not neglected in the program, chaired as the Centennial Committee was by James Hawkinson. A “Centennial Lecture Series” offered biblical, theological, and historical lectures on Covenant identity, the latter given by historians Zenos Hawkinson, Karl Olsson, and Glenn Anderson. The Commission on Covenant History led an oral history workshop, crafted an anniversary exhibit, and formed a new Heritage Society. However, President Engebretson’s attention to history in his address is minimal and generic, the focus instead on the future. The keynote address during the “Heritage Service” was delivered by Krister Stendahl, newly appointed bishop of Stockholm in the Church of Sweden, who urged the Covenant that the way forward was to enter its second millennium, leaving behind its Swedish past and carrying with it its immigrant roots.

By and large, the denomination followed Stendahl’s advice. Speaking at the 1994 Covenant Midwinter Conference, Paul Larsen, now president of the denomination, told the gathered pastors in a transcribed aside: “One of our problems is we’ve got to start rethinking ourselves apart from our Scandinavian roots.” This conviction expressed from the Midwinter stage was indicative of the denominational trajectory as the Covenant moved into its second century

Telling Our Story at 150 (2035): “Page Not Found”?

We are only a decade away from the 150th anniversary of the Covenant. What projects will be commissioned and undertaken to narrate the past half-decade of history? What sources will we have to tell that history? The Covenant has changed significantly since 1985, both in the sheer numbers of newly planted and adopted churches as well as in our becoming more fully a multiethnic mosaic community. Our total congregations have grown from 584 in 1985 to 856 in 2024. At the Covenant’s 125th anniversary in 2010, the proportion of Covenant congregations classified as “ethnic” or “multiethnic” had jumped from 3.5 percent to 25 percent. According to information provided by Paul Lessard, recent vice president of mission priorities, that proportion currently stands at 36 percent. Strikingly, more than half (51 percent) of all congregations recorded in 2024 were organized after the 1985 centennial, with 38 percent organized after the turn of the twenty-first century.

As it has in the past, these shifts have brought further questions regarding Covenant identity and Covenant historiography—among them the creation of the Fivefold Test in 2004 and its expansion in 2020 to the Sixfold Test, both of which call for a commitment to “purposeful narrative,” as discussed above. Unfortunately, however, the call to purposeful narrative has coincided with a convergence of shifts in communication, publications, record keeping, and record preservation that jeopardize our capacity to tell any narrative at all. As I have sought to show, as a denomination our historians have drawn from a deep well of publications, meeting minutes, correspondence, and denominational journalism, all preserved through high standards of archival practice and dedicated archivists—a well that is not being replenished in ways that we must address proactively if we desire to actualize purposeful narratives.

The primary duty of an archive is to preserve historically significant records indefinitely so they can be accessed indefinitely by researchers to support historical knowledge and interpretation. However, it is a prerequisite that records be sent to the archives—the communal action pleaded by the History Commission across its history. Since our centennial in 1985, fewer and fewer records have been transferred to the Covenant Archives and Historical Library. As one example, compare the presidential records currently held in the Covenant Archives, measured in linear feet of shelf space. Even accounting for relative term lengths, noted in parentheses, the trend is clear.

- W. Anderson (1933–1958): 60 linear feet

- Clarence Nelson (1958–1966): 26 linear feet

- Milton Engebretson (1967–1985): 33.75 linear feet

- Paul E. Larsen (1986–1997): 41 linear feet

- Glenn R. Palmberg (1997–2008): 11 linear feet

- Gary B. Walter (2008–2018): 1.5 linear feet

- John Wenrich (2018–2022): 0 linear feet

The shift to digital communication and record keeping provides a partial explanation of this trend, alongside shifting practices of administrative staffing. The papers of President Engebretson, for example, include copies of (seemingly!) every letter he received as well as his responses, copied, filed, and delivered to the archives by his assistant, Karen Farmer. His papers include meeting minutes and articles—likewise collected, organized by year, and transferred to the archives by his assistant.

Of course, postal mail was not the primary means of communication for either President Walter or President Wenrich but rather email. However, no presidential emails have been transferred to the archives for preservation. (By contrast, consider that the National Archives and Records Administration accessioned 200 million emails from the Bush Administration!) How many important decisions, conflicts, and deliberations take place within email—or even text message? How will that information be preserved and made accessible for researchers? Without these records, what is lost in our understanding of what led to and resulted from key actions and decisions taken during these decades of significant challenge and change?

Correspondence is only one preservation casualty of the digital shift. Consider websites where information is updated as it changes, simply replacing (i.e., erasing) prior records. If covchurch.org is our primary source of denominational information sharing, for example, what record will we have of earlier explanations of departments, initiatives, values, identity, and decisions as webpages are updated? In the process of writing this article I looked for the webpage describing the 2004 Fivefold Test, which I had cited in a 2020 essay. Rather than finding this record, I received the ominous message that summarizes the digital dilemma: “Page Not Found.” The same is true for conferences and congregations. To what extent does your church rely on its website for information sharing, and how would you access information from five or ten years ago that was shared in this medium? How, fifty years from now, would a historian be able to learn about your present congregation or ministry?

In an age of digital communication and web-based information sharing, we can take for granted the sheer abundance and immediate accessibility of information (and disinformation) around us. However, this can blind us to the true fragility of digital records. The preservation of paper records entails measures such as acid-free storage boxes and temperature-controlled spaces, removing staples, lamination or perhaps digitization if the physical condition is too degraded. The preservation of—and enabling access to—digital records is far more challenging as archivists handle hundreds of file types, triage against media obsolescence, and navigate proprietary restrictions. And these are the challenges for the born-digital records that make it to the archives!

The need to systematically address digital records management and preservation is urgent, but it only provides a partial explanation for our diminished archival collection. Also at root is a concurrent contraction in denominational journalism, publications, and record keeping. Consider the contraction in publication frequency of our primary denominational publication, The Covenant Companion—at one time published weekly, the magazine is now printed biannually. Explore the extensive reports and Annual Meeting minutes available in Covenant Yearbooks until the mid-1990s through the Frisk Collection of Covenant Yearbooks, and compare the level of detail in reports and meeting minutes in these volumes to the most recently available yearbook from 2023. Fortunately the decision made to discontinue the yearbook entirely has been reversed! Nevertheless, the resulting gap in public records for 2021 and 2022 points to the critical importance of these denominational records for historical knowledge—and even now these records are not publicly accessible but password protected, available only to Covenant ministers.

This is not to wax nostalgic for a bygone era but to recognize the concrete, communal actions that, in aggregate, either enable or preclude historiography. If these trends continue, we may have very little for a future Covenant historian to draw upon as they seek to answer critical historical questions of our time.

To offer one example of how these trends converge, in 2019 I wrote an article attempting to reconstruct the Covenant’s reception of and response to the Black Manifesto fifty years prior. Through extant records—detailed commission reports and statistical records published in the Covenant Yearbooks; archival collections of meeting minutes, extensive correspondence, articles, and reports; and preserved publications like The Covenant Companion—I was able to trace the spread of knowledge of the Manifesto, conference and denominational responses to the Manifesto, resultant Annual Meeting action to create a new “relief fund for Black America,” reactions both negative and positive to this action, and the mixed success and long-term evolution of the fund. This is one very small example of how history writing happens. It was my best attempt to answer questions posed by Covenant history students regarding how the Covenant as a denomination positioned itself within the civil rights movement and black power movement. Certainly, my interpretation could be critiqued or expanded, but it was only possible because sources were available. And they were only available because they were created by the denomination and then sent to the archives for preservation.

To what extent will a historian in 2100 be able to answer the question, “How did the Covenant respond to the Black Lives Matter movement?” or, “How did the Covenant respond to the legalization of same-sex marriage?” in all the complexity and rich context we who have lived through these decades know these answers to hold? How will they explain the significant movements of church growth—church planting and adoptions—that have indelibly shaped our denomination? What sources might they want to access to reconstruct or ascertain? Perhaps our social media posts that can be deleted? Our web-based articles that even now are difficult to find and easily replaced or eliminated? Email correspondence that is not collected or archived? This is especially acute when we remember the vast proportion of Covenant congregations organized after the digital shift.

As we approach our 150th anniversary as a denomination of the Evangelical Covenant Church, we must demonstrate our commitment to purposeful narrative by building the infrastructure of record creation and preservation that will enable it, now and for future generations. On this point I find the words of Wilma Peterson appropriate: “I think we have a great responsibility for how we leave the world for the next generation and the generations to follow.” Here are some very basic action steps to this end:

- Communal history writing. In the spirit of Covenant Memories, every congregation, regional conference, commission, association, and mission priority should appoint a team committed to narrating your history as a contribution to our collective story. What projects can be done to tell your ministry’s story? A short anniversary history? Biographies of key leaders and turning points? An oral history project?

- Source collection and preservation. As this first goal is pursued, the prior work of identifying sources will immediately emerge—and this is an opportunity for a second, perhaps even more important task: collecting and preserving sources. Identify what sources already exist and whether they are being cared for. Are they protected, organized, and accessible? Identify what additional sources are needed and should be collected. Can you build a congregational archive—or send your records to the Covenant Archives and Historical Library for preservation?

- Records management policy. It is a matter of urgency that denominational leaders support the creation and execution of a records management policy that specifies what types of records are preserved and on what schedule they are transferred to the archives for preservation. Of special urgency is a policy for digital records preservation, including email, web content, and social media. This requires financial support for our archives and archivist to develop these guides and access the enormous volume of material it would rightly generate.

- Recommitment to robust record keeping and publications. The fullness of future historical knowledge depends on our current commitment to robust, transparent record-keeping (e.g., detailed annual reports and meeting minutes that are publicly available) as well as commissioned publications, including magazines and books. Can we reinvigorate Covenant Publications?

Now is the time to commence this work so that when we come to the 150th anniversary of the Covenant, we can celebrate the full mosaic of our body.

As we anticipate the coming anniversary, we need “histories,” yes. But even more urgently, we need to shore up the much broader network of source creation and preservation that supports the writing of history. This is essential if historiography is to remain a possibility for the next generation of Covenanters: that the decisions, actions, and responses to internal and external challenges and opportunities that we are making now are available to the next generation. This is a responsibility we bear together, and only together can we adequately acquit it. While one person may write history, source creation and preservation are communal commitments.

The real evidence that a community is committed to purposeful narrative is not the assertion of that commitment—nor even critiques of past or possible histories—but the corollary commitment to active creation and preservation of sources. Without sources, there is no narrative. This is a practical problem, but it is also a spiritual one. Cicero wrote that “To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain forever a child.” Every child believes the world began with them, and every parent knows this to be false. If we do not attend to our history as a denomination—if we come to questions of identity as though we are the first to be asking them—we replicate this childish myopia that is so prevalent, even championed, in our time. We need historical understanding to inoculate us from the myth that what is new to us is new per se, from the poor stewardship that reinvents wheels rather than wisely stewarding the past toward the future.

Conclusion

We are indebted to the hundreds of Covenant history keepers—historians, lay and professional, archivists, and translators—whose careful, faithful work has enabled the rich historical record we steward. And we bear the responsibility to those who follow us to ensure they will be able to understand, critique, and learn from the decisions we are making right now that are shaping the church they will inherit from us. Whether the next generation will be able to tell a purposeful narrative depends on our creation and preservation of sources today.

In his 1935 presidential report, T.W. Anderson wrote, “To attempt to review the history of the five decades that have passed since the inception of the Covenant in February 1885, would be superfluous. In our Jubilee volume, Covenant Memories, the challenging perspective is given. This book should find its way into every Covenant home to be read and appreciated.” May our Covenant president in 2035 be able to likewise say that a review of the five decades since 1985 would be superfluous, considering the work we have done together as Covenant history keepers!

Note: This article was first published in the Covenant Quarterly. To view the original publication, visit Covenant Quarterly.